by Suzie Ewing Nacar

Charles and Louise Ewing were friends with the novelist Kenneth Roberts, one of Kennebunkport’s most famous native sons. They socialized together both in Kennebunkport and at Timber Point. They worked together on a famous (or infamous) civic/artistic issue related to the Kennebunkport post office, and Roberts called on Ewing to assist him with his various architectural projects. One of these architectural pursuits was crucial to Roberts’s establishing a place where he would do some of his best writing. The episode provided grist for his mill.

In case you are unfamiliar with Kenneth Roberts, he is best remembered as a writer of vivid and impeccably accurate historical novels, set (approximately) during the American Revolutionary War period. Born in 1885, Roberts began his career as a reporter for the Boston Post, served in the American Expeditionary Force in Siberia, and returned to work for the Saturday Evening Post. Roberts had three ancestors who served in the siege of Louisburg (near Quebec) in 1758. He had ancestors who fought at the battles of Ticonderoga, Hubbardston, and Saratoga in 1777, and were encamped at Valley Forge that winter. (Coincidentally, Ewing’s great-grandfather George Ewing was also at Valley Forge.) Roberts wanted to know more about their lives and circumstances. History books left him “disgusted:” the characters were “cardboard people, flat, unreal, bloodless, lifeless …. The little people like my great-great-grandfathers and all those other men from Maine, who sailed the ships and stopped the bullets and cursed the rotten food and stole chickens and wanted to get the hell out of there and go home — they just didn’t exist at all.” (I Wanted to Write, p. 167.) Roberts decided, around 1927, that he had to assemble all the facts himself. He would start with an account of the long trek to Quebec led by Benedict Arnold, following a fictional character from Kennebunkport based on one of his forebears. He needed a place to write undisturbed.

At this point, Roberts’ editor George Lorimer of the Post sent him to Italy to cover political developments there. On the way home, he and his wife Anna visited her sister Katherine who had married an Italian doctor, Pio Pediconi. They picnicked at a property that the Pediconis owned near Orbetello, on a promontory overlooking Elba and Corsica. Roberts had a eureka moment: “… I awoke to the fact that this was it! This, as Brigham Young said to his Mormon followers when they descended from the mountains to the shores of Great Salt Lake, was The Place!” (I Wanted to Write, p 180). Roberts offered to renovate and furnish the farmhouse in exchange for having the use of it during winters for writing. The offer was accepted.

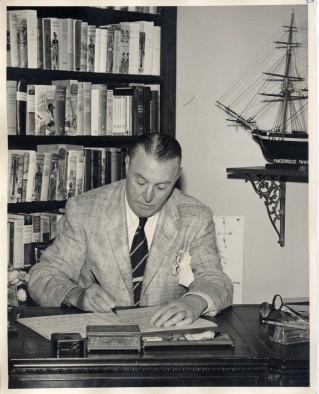

Here is where Charles Ewing is brought into our tale:

When, in the following autumn, I decided to return to Italy and devote a winter exclusively to writing, I paid a hurried visit to a distinguished New York architect, Mr. Charles Ewing, and placed my hopes and fears before him. With me I had a photograph of the pink farmhouse — a photograph two inches wide and three inches long.

After studying the photograph through a magnifying glass, Mr. Ewing asked the dimensions of the farmhouse. I was unable to tell him. He then observed that the house appeared to have no chimneys. We obtained a larger magnifying glass and scrutinized the photograph with even greater care, but the chimneys persistently remained hidden ….

Mr. Ewing at last gave it as his opinion that what I wished to do would not be difficult, since labor was cheap in Italy, and masons were plentiful and skillful. He had been given to understand, he said, that one only needed to show a group of Italian masons a picture of what one wanted in order to get it; for not only were they themselves masons, but their fathers before them had been masons, and their grandfathers and great-grandfathers as well — skilled masons, all of them, with a passionate love of beauty.

Since this coincided with my beliefs, I went away in a contented frame of mind; and when I returned on the following day, Mr. Ewing and his head draughtsman had evolved plans calculated to make an Italian farmer throb with pleasure …. (“The Half Baked Palace”, in For Authors Only, pp 84-85.)

Roberts reported on the progress of the “American Wing of the Half-Baked Palace” in letters to Ewing:

I took pictures of the house from all angles yesterday and they are being developed in Rome today. The prints should be back day after tomorrow, and I will send them to you to give you a better idea of the place …. Pio is awestruck at the skill with which you were able to do such a beautiful piece of planning with nothing but a small and imperfect snapshot to go by, and has asked me to express his admiration to you …. I have wished many times that you could be here with us; for I know that a thousand ideas would present themselves to you immediately. (Letter from Roberts to Ewing, February 1928.)

Later that same month, Roberts writes: “The contractor says that the roof will be on and tiled by a week from today. It looks bully, and the Pediconis are tickled to death. Word of this unbelievable … American ability to draw an addition to an Italian farm-house in New York, without ever having seen the house, has been spread far and wide over Rome by Pio, and has amazed all Roman society ….” (Letter from Roberts to Ewing, February 1928.) Roberts sent photos and sketches to Ewing several times during February and March, as Roberts wanted Ewing’s advice about necessary modifications of the plans.

The actual carrying out of Ewing’s plans was a series of adventures that Roberts wrote about in his essays “The Half-Baked Palace” and “When in Rome –” for the Saturday Evening Post, later collected into his book For Authors Only. He related additional details to Ewing, including his dealings with the Italian contractors, some of which illustrate his famous temper.

One memorable scene, not atypical, is worth quoting:

… we have had to fight to make them leave the old bricks on the threshing floor. This, to them, is the crowning absurdity. They are old, nicely colored, thin bricks. They built 150 of them into the walls of the house before we knew what was happening. A week ago, they took some loose ones that I had salvaged, & I blew up. The blow-up became an explosion when I heard Pio condescendingly explain in Italian to the contractor that his sister- and brother-in-law wanted things exactly as they had them in America. With Katherine interpreting word for word, including the profanity, I waved my arms and howled that we were trying to give them the things that made Italy beautiful: that Italian architects followed the bastard styles of Germany and France and England and built the most atrocious villas that the world ever saw: that the beauties of the old town of Porto Santo Stefano were being sacrificed to the stupidity of people who couldn’t see beauty when it was jammed down their throats; and that in order to get architects who knew how to utilize the beautiful things of Italy, one had to go to America, 4000 miles away. (Letter from Roberts to Ewing, March 1928. Emphasis mine. Note: “Bastard architecture” refers to mixing style elements that would not have been combined in original forms, such as adding balustrading to a classical Greek building – balustrading would be appropriate for a classical Roman building, never Greek.)

The result of that first winter’s literary labor, a draft of the novel Arundel, was followed by about eight other historical novels, probably most of them given a solid start at the Italian villa. Of these the best known, Northwest Passage, was made into a movie. Kenneth and Anna Roberts spent 10 winters at the Half-Baked Palace.

It took several years for the Robertses to get the house plumbed, heated, and furnished to their satisfaction (though Roberts drafted several novels there wrapped in blankets in the intervening winters). In February of 1935, Roberts wrote:

Well, the chief idea of this letter is to let you know that we are enjoying the place tremendously, and that it is now worth all the agony and nervous energy that we expended on it last year; though at the time I thought I’d have to live here until my long gray whiskers could be tied three times around the Isles of Shoals before our labor could be repaid. I wish that you and Louise could drop in on us for a few days and see the results of your planning. I’m sure that you would be very much pleased; and I know that you would realize how very grateful we are. (Letter from Roberts to Ewing, February 1935.)

Ewing’s architectural expertise was also tapped by Roberts on behalf of his mother: “I think, come June, that when you drift over to the Beach [Kennebunk] again and see how we carried out your ideas on altering Mother’s house, you will be pleased. … everything is exactly as you said to do it, except for the bathrooms, where we didn’t use enamel paint above the base-boards, but compromised on a pale stain, on acc’t of getting panicky over expenses ….” (Letter from Roberts to Ewing, February 1935.)

Ewing and Roberts were key players (along with Booth Tarkington) in what Roberts called the “Great Post Office Stink” in which they were successful in removing the original Elizabeth Tracy mural “Bathers” (done as part of the New Deal Public Works of Art Program) and having it replaced with the one there now by Gordon Grant (a friend of Ewing’s). But that will be a story of its own.

References

• Roberts, Kenneth, I Wanted to Write. Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1949.

• Roberts, Kenneth, For Authors Only and Other Gloomy Essays. Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1935. The two essays about the Italian Villa are “The Half-Baked Palace” and “When in Rome–“.

• Letters from Kenneth Roberts to Charles Ewing, from the Ewing family’s private collection and from the Kenneth Roberts papers at the Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.